Safflower plants: enabling a bio-based industrial economy

By Aaron Stone

In July 2015, GO Resources and Australia’s National Science Agency (CSIRO) announced a significant development in the Australian oilseed industry, a worldwide exclusive deal for commercialisation of technology to produce super high oleic safflower oil (SHOSO). The deal primarily focuses on the high value industrial oil and oleochemical market estimated to be worth in excess of USD30 billion globally.

Fuel & Lubes International spoke to GO Resources Chief Executive Officer Michael Kleinig to ascertain progress on the commercialisation of SHOSO.

“The research phase is now complete and we are very close to filing the dossier for deregulation to the OGTR (Office of the Gene Technology Regulator) for approval,” advises Kleinig.

He says the company is on track to commence commercial plantings in July or August 2018 as per previous guidance, and expects to harvest the first commercial oil in January 2019. Kleinig anticipates the company will generate its first revenues in the second quarter of 2019.

GO Resources is currently undertaking a Series A round of venture capital financing to support commercial rollout of the super high oleic bio-based project. A previous announcement, on February 28, 2017, confirmed it had secured assistance from the Australian Government’s Cooperative Research Centres (CRC) programme, in the form of a AUD3 million (USD2.25 million) grant.

The rising demand for renewable, sustainable and environmentally friendly feedstocks from governments, producers and consumers clearly presents a substantial opportunity for plant oils. The use of plant oils has become increasingly prevalent in transport fuel applications such as biodiesel, and although development in bio-based alternatives are welcomed, realistically the ability of plant oils to make a significant dent in the estimated 1.5 billion metric tonnes per year global demand for transport fuels is perhaps somewhat limited. Non-carbon based renewable energy sources are clearly more scalable.

Plant oils are a worthy renewable alternative to petroleum in a variety of industrial chemicals, primarily due to their analogous linear carbon chain structures to common petrochemicals used in the industry. Soybean, canola, olive, sunflower, oil palm, cottonseed and corn are all major food oil crops used for industrial applications. Currently, safflower plays only a minor role in industrial use.

The safflower plant (Carthamus Tinctorius) is an annual broadleaf crop from the Compositae or Asteraceae family. Referred to as “kusum” in India, and “hongua” in China, it is native to many parts of Asia, the Middle East and Africa, and cultivated in approximately 60 countries throughout the world. India is the largest producer, followed closely by several Western U.S. states, and Mexico.

The safflower plant (Carthamus Tinctorius) is an annual broadleaf crop from the Compositae or Asteraceae family. Referred to as “kusum” in India, and “hongua” in China, it is native to many parts of Asia, the Middle East and Africa, and cultivated in approximately 60 countries throughout the world. India is the largest producer, followed closely by several Western U.S. states, and Mexico.

Long rumoured to hold medicinal qualities, safflower is one of the world’s oldest crops, dating back 4,000 years to Ancient Egypt. Today it is primarily grown for its oil production with common uses in cooking and food preparation, although the crop has low local demand in Australia owing to its current oil quality. “Most of Australian crop is grown for birdseed and use in Japanese food products,” says Kleinig.

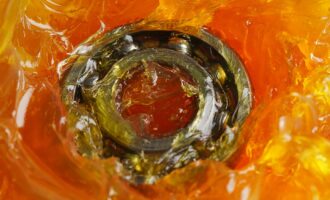

Safflower grows roughly 5-foot-tall in dry, arid climates. Its ‘thistle like’ head contains 20-50 seeds and produces two different types of safflower oil, a high oleic safflower oil, and linoleic acid safflower oil. The high oleic variety is attractive as a petroleum replacement owing to its high oxidative stability, biodegradability and is already consumed for manufacture of some plastics, cosmetics and lubricants.

Several plant oils offer a valuable source of oleic acid, although safflower seeds boast the highest level of purity of the fatty acid.

The problem restricting widespread adoption of plant oils in industrial applications is many possess high levels of polyunsaturates, which can become unstable. Separating polyunsaturates during oil processing is costly and problematic. While safflower contains a high 75-80% desirable oleic acid levels, the remainder is undesirable polyunsaturates and saturates.

The Crop Biofactories Initiative (CBI), formed in 2004, established a strategic alliance between CSIRO and the Grains Research and Development Corporation (GRDC). The two companies set about jointly overcoming this issue. Using gene silencing technology, otherwise known as RNA interference, the researchers successfully raised oleic acid levels in safflower oil to 92%, while reducing unwelcome polyunsaturates.

The technology first appeared in 2012. A statement in April of that year by Allan Green, deputy chief of CSIRO Plant Industry, declared “we have succeeded in dramatically lowering the polyunsaturates to below 3%, thereby raising the monounsaturate oleic acid to over 90% purity.”

Gene silencing technology stops the conversion of oleic acid to other fatty acids. This highly significant development has delivered the highest purity of oleic acid and the most unsaturated oil available in any commercially-scaled crop.

Gene silencing technology stops the conversion of oleic acid to other fatty acids. This highly significant development has delivered the highest purity of oleic acid and the most unsaturated oil available in any commercially-scaled crop.

A CSIRO report in 2012 asserted that “should the super high oleic safflower be commercialised, then Australian grain growers will have a unique opportunity to produce and supply renewable, sustainable plant oils for industrial use, and these oils could one day replace petrochemicals in industrial products ranging from fuel and lubricants to specialty chemicals and plastics.”

After a successful expression of interest and license negotiations, GO Resources was chosen by CSIRO as the preferred partner to commercialise technology for the high-value industrial oil market. GO Resources Pty Ltd is an Australian clean technology business, set up three years ago, specifically to commercialise this opportunity. The company has expertise in deregulation of GM technologies, industrial lubricants and oleochemicals, and the development of supply chains for GM products.

Kleinig, also a founding director of GO Resources, says the diverse array of industrial applications for SHOSO include lubricants, plastic additives, biofuels, resins and polymers, cosmetics and solvents. The profile of SHOSO means minimal additions are required before it can be used industrially. GO Resources’ primary focus for the industrial grade oleic oil, post successful deregulation, is the North America and Asian markets.

“GO Resources will target the higher value/higher margin industrials markets where the superior functionality and quality of its super high oleic oil are valued and in demand by customers and will bypass the low value end markets where price is a key driver of demand,” says Kleinig.

“The availability of a plant oil at these super high levels of oleic acid to the industrial market at a price that can make bio-based products commercially viable has the potential to be a game changer in this sector,” he adds.

Despite a clear emphasis on industrial grade oil, high oleic is also valued by the food services sector due to its stability and high burn point. As part of the submission process for deregulation, Kleinig says the company is also seeking Food Standards Australia New Zealand (FSANZ).

While only 2,500 hectares (ha) will be established during the Initial commercial plantings in July-August 2018, the company advises the forecast to grow to 100,000 ha in Australia by 2020 is still appropriate, after which they will look at global supply opportunities, most likely plantings in the United States and Canada in 2020 and 2021.

Right now Kleinig and his team’s efforts are focused on compiling a complete agronomy package to assist farmers in maximising farm production of this new oil crop in Australia.