Lithium battery recycling: We have a problem

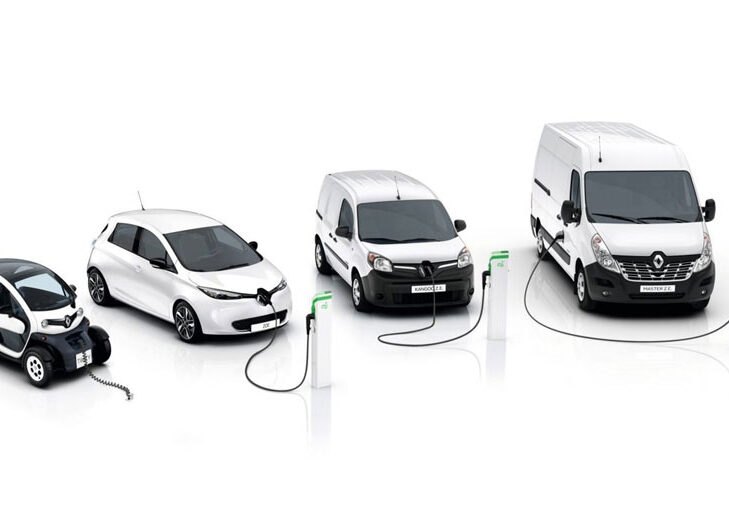

Australia, “we have a problem”. This, according to a Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organisation (CSIRO) report on lithium battery recycling released in April of this year. Lithium-Ion battery (LIB) waste is growing at more than 20% per annum, fuelled by skyrocketing demand for rechargeable electronic equipment and the onset of electric battery powered vehicles.

This could be but the tip of the iceberg. Australia is yet to hit full throttle on electric vehicle (EV) adoption. As of June 2016, EVs accounted for a paltry 0.15 % of new car sales, with a grand total of 4,500 EVs on Australian roads. Globally, EV interest is increasing, many predicting the technology will surpass internal combustion engine vehicles in the not-so-distant future. With an influx of EVs into Australia comes an even greater stream of LIB waste.

EV batteries have an estimated life expectancy of 10 years. As such, a large proportion are yet to reach end-of-life in Australia. Nonetheless, in 2016 Australia generated 3,300 tonnes of LIB waste. Most of this extremely hazardous waste was disposed of in landfills — posing potential environmental and human health implications. A mere 2% was collected and exported offshore for recycling. The CSIRO report predicts LIB waste will climb sharply to between 100,000 to 188,000 by 2036, a growth rate of 12% per year.

The economic loss of disposing of or exporting LIB waste is also of concern. There’s money in waste. One tonne of battery waste holds a potential recoverable value of between AUD 4,550 and 17,252 (USD 3,345-12,683), and the CSIRO report estimates an economic loss of between AUD 813 million and 3 billion by 2034 (USD 597.7 million-2.2 billion), based on current day prices.

Sometimes, with problem comes opportunity. Scientists at Australia’s national science body set out to review the current status and opportunities associated with LIB waste. Their report concluding that an onshore, local LIB recycling industry to counter lithium-ion battery waste is economically and environmentally achievable – with the potential to become a recycling hub for feedstock sourced from neighbouring countries such as New Zealand.

Australia has a well-defined process for recycling nickel/cadmium batteries, yet no such practice exists for recovery of value from LIB. Existing recycling schemes rely on scrap metal recyclers to break down waste for export — foregoing the opportunity to recover lithium or the critical metal cobalt. Cobalt, in particular, enjoys high commodity prices — driven by the vulnerability of supply. Half of the global production of cobalt comes from the Democratic Republic of Congo — a region where armed conflict, illegal mining, and human rights abuses are prevalent. A variety of additional battery resources hold potential for recycling such as copper, zinc, nickel, iron, aluminium, plastics, electrolyte materials, and technical materials such as graphite.

A 2016 report by Swain entitled Recovery and recycling of lithium: A review identified Australia as the highest producer and exporter of lithium, totalling 40% of global supply. Despite strong lithium mineral reserves, Australia lacks the technology and infrastructure to manufacture technical grade lithium products, such as batteries. However, the Australian Mining Executive Council (AMEC) recently identified “a significant opportunity for Australia to become a market leader in the manufacture of these products.” Such a move would not only enhance Australia’s lithium value supply chain but also provide an onshore end-user for secondary lithium recovered from LIB recycling.

Data in the recently released CSIRO report data includes six formal stakeholder reviews, supplemented by a comprehensive literature review and knowledge derived from several academic conferences. While the national science body is quick to acknowledge the potential impacts of a small sample size, the authors confirm interviews capture 43% of the LIB recycling and collection industry. All participants were in agreement that Australia had a “moral obligation to directly manage its own waste and this necessitated a domestic processing option.” However, interviewees cited a variety of barriers to achieving a domestic LIB recycling solution, most notably a lack of policy.

Policy and regulation are central to resource recovery from LIB wastes in world leading countries and include bans on landfill disposal, resource recovery targets from specific waste streams, and incentives or penalties for manufacturers and distributors. Incentivising the adoption of EVs will also provide a meaningful increase in the stock of second-life and end-of-life batteries for recycling.

A lack of consumer awareness of the environmental impacts of LIB waste and limited understanding of recycling options was a key finding in the CSIRO report. Survey participants acknowledged the need to address critical information gaps to develop a successful LIB recycling industry and called for “plain language, best practice guidelines for the transport of end-of-life LIB, applicable to the Australian market.”

A voluntary recycling program modelled on the Mobile Muster program — introduced for mobile phone recycling – held the greatest support from interview participants, most suggesting manufacturers incorporate the cost of end-of-life recycling in their product pricing as the originating cause of Australia’s landfill problems.

Costs associated with import and export of battery waste were recognised as a deterrent to Australia becoming a regional LIB recycling hub. The absence of collection infrastructure and the high cost of collection were major concerns pertaining to the economic feasibility of domestic processing. Australia’s sprawling landscape and small, widely dispersed population centres result in a high cost of transportation. Sorting and dismantling LIB is also a significant challenge when processing battery wastes. Further, participants opined that current collection rates of LIB waste are too low to support local recycling initiatives.

Despite these noteworthy barriers, lithium battery recycling is an emerging industry in Australia. LIB wastes are in the process of being banned from landfill in some states, and new recyclers are beginning to develop a footprint. One such example is Neometals, a company with lithium mines in Mt. Marion and a Lithium hydroxide production facility in Kalgoorlie, which plans to construct a commercial lithium battery recycling plant in Western Australia in 2019.

A step removed from recycling is reuse. Once EV batteries reach end-of-life in vehicles, they may be repurposed for energy storage or a “second-life.” Many EV manufacturers are already investigating energy storage partnerships. Relectrify is a company looking to take advantage of this growing global opportunity. The Melbourne-based start-up aims to facilitate the transition of batteries into a second life in residential solar storage, commercial peak-shaving and grid support.